Effective training for ground operations necessary for skill set

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 29 May 2015 | Tim Meagher | 1 comment

Tim Meagher, Ground Operations Inspector with the Civil Aviation Safety Authority of Australia (CASA) examines the changing face of ground operations and how training can be optimised to ensure safety and make the most of changing skills demands.

The ground operations sector has experienced significant changes in the past 10-15 years because of changes in the utilisation of resources in the aviation industry. This includes a reduction in aircraft turnaround times, changes to staffing levels, an increase in the level of outsourcing, and the use of new technologies and equipment. Additionally, newer aircraft require less maintenance so not all airlines have an engineer at each port. As a result, tasks such as receipt and dispatch, which were previously only carried out by engineers, have now become commonly accepted as ground operations functions at many airports.

The majority of academic research and literature relating to training in aviation focuses on the training of pilots, cabin crew and engineers. These workers represent the final layers in the defence against disaster and are governed by a range of legislation to ensure training is effective. Literature and research on training for ground operations staff is limited, despite ground staff playing a key role in preventing unsafe situations from arising.

The term ‘ground operations’ encompasses the non-maintenance tasks carried out whilst an aircraft is on the tarmac before and after a flight. This includes a wide range of workers, such as aircraft fuellers, baggage handlers, ramp agents, aircraft cleaners, caterers, customer service staff, load controllers and flight dispatchers.

These roles are generally regarded as being semi-skilled, with the obligation of staff training resting on the employer rather than the employee, as occurs with pilots or engineers. These other sectors of the aviation industry have recognised licencing and/or accreditation systems in place. What this means for ground operations staff is that when an employee moves from one company to another, in most cases, re-training will be required.

The Flight Safety Foundation estimates that ramp accidents cost major airlines US$10 billion per annum1, while a 2004 paper by Vandel2 shows there are a higher number of lost workday cases in commercial aviation than occur in the mining or construction industries. In most industries, suitable training for staff has been recognised/identified/recommended as the most effective control in preventing injuries and accidents. Whilst in ground handling there is generally an understanding that an effective training system is a strong contributing factor in ensuring a safe environment for staff, aircraft and passengers, there is often not a clear understanding of what constitutes effective training and how this can be achieved.

Challenges in achieving effective training

There are a number of challenges that must be overcome by ground handling agents in order to implement an effective training system. One of the common challenges is the complexity and variability of the service offerings required by the different customers of a ground handling agent. For example, a typical ground handler with five airline customers may provide each customer airline with a different combination of services (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Examples of different product offerings of a ground handling agent to various airline customers

A staff member who performs a task (e.g. aircraft pushback and towing) will generally perform this task across all airlines that the agent handles. In most cases this results in each staff member completing a separate training course for each airline handled, which includes memorising particular sentences required by each different airline. It is customary for each staff member to perform other duties as well (e.g. baggage loading, tug driving, aircraft loading) requiring further training from each airline. This creates cost pressure on the ground handling agent because of the hours it takes to deliver training and the administrative burden. This could result in a financial inducement for a ground handling agent (GHA) to provide the minimum level of training in the quickest and most cost effective means possible. As such, training is delivered in a way that is compliant, but is not always effective in ensuring that all staff members have the necessary skills and knowledge to perform their tasks.

The other major challenge to implementing an effective training system for a ground handler is purely financial. Whilst an effective training system may save money through reduced staff turnover, minimising errors and improved service delivery, it requires an investment of money into initially training staff. An organisation will be required to have particular financial strength to accept the cost of training up front with the aim of achieving a saving in the future. In some organisations there is a strong focus on achieving short-term financial goals, resulting in long-term benefits being missed. There is a quote from an unnamed change consultant that nicely sums this up3:

The question to ask is not what if I spend all of this time and money training and developing a person and they leave? Rather it should be what if I don’t spend any money on their training and development, and they stay?

Ineffective training: A case study

During the turnaround of an Airbus A320, a ramp team of three were performing the ramp handing functions. One of the staff was allocated to drive the baggage tug throughout the turnaround. This involved bringing the rolling stock to the aircraft, taking the inbound bags to the bag room, bringing the outbound bags to the aircraft and removing the rolling stock. Each time the staff member approached the aircraft he did so at a considerable speed, and without performing a required brake check. This is a clear breach of both the airline and GHA’s policy for driving within the circle of safety around aircraft, with the slow driving speed and brake check designed to reduce the likelihood, and consequence, of contact between the baggage tug or ground support equipment and the aircraft.

In a debriefing after the turnaround the driver was asked if he could explain in his own words what he understood of the procedures for driving around aircraft. The staff member was not able to explain what any of the requirements were. When asked to describe what the circle of safety is, and how this changes the way a tug is driven around the aircraft, the staff member remembered that the topic was covered in training and he remembered a question on it in the test, but he did not know what this meant for driving in practice. He then suggested that he would be able to figure it out if given multiple options to select from, as he was used to answering multiple choice questions.

The training material provided did describe the correct procedure for driving around the aircraft, and was presented via PowerPoint to the class of new staff. This staff member had completed the training within the past three months. Competence was assessed using a multiple choice assessment that covered a wide range of tasks. In the assessment there was only a single question related to how to approach an aircraft with a baggage tug.

In this instance the completion of the training had not resulted in a staff member with the required knowledge to perform the task. The assessment process had also failed to identify that the staff member was not able to competently perform the task. This created a latent failure within the systems of both the airline and the ground handling agent.

From a financial point of view, in this instance the ground handler has borne 100% of the cost of training, but has received none of the benefit of a safer work environment or reduced risk of damage to an aircraft that would have derived from improved conformance to procedures. In this way ineffective training represents a very poor return on investment.

Effective training cycle

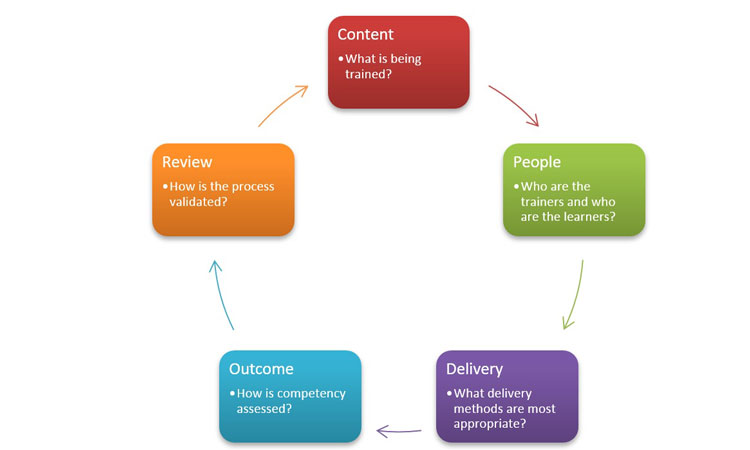

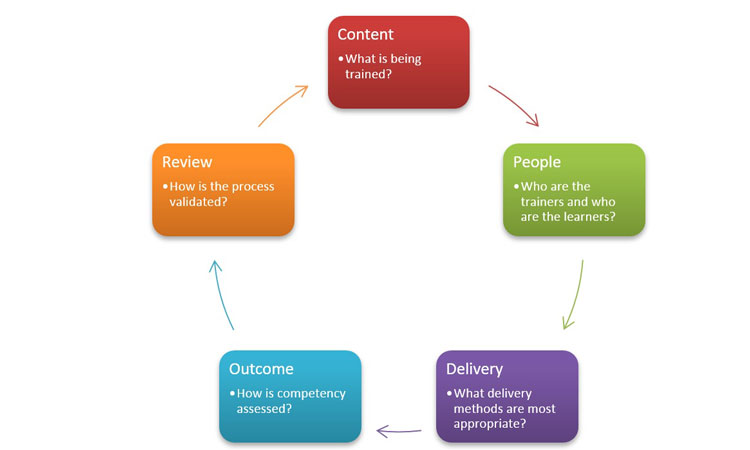

The existence of a learning culture with a commitment to continuous improvement is a crucial component of a safety system4. This section aims to present the ‘Effective Training Cycle’ (Figure 2) as a toolkit to help ground handers implement an effective training system, by reviewing the effectiveness of the training undertaken. The A320 turnaround case study described above will be used to illustrate the strategies that can be implemented to improve the effectiveness of training undertaken by a ground hander. The key to this toolkit is that it is an ongoing cycle, representing the fact that an organisation must remain open to feedback and continuous improvement in order for training to remain effective.

Figure 2: The ‘Effective Training Cycle’

Content: What is being taught?

The content section of the cycle challenges the ground handler to consider what content is required in the first place. A Training Needs Analysis is a useful exercise for determining what skills and knowledge are required by different groups of workers. Once identified, the training should include a range of complimentary technical and non-technical skills. The technical skills should be based on the documented procedures in the operator’s manuals. In the case study the content being training was consistent with the operator’s manuals, and was delivered to the appropriate staff groupings.

People: Who are the teachers, and who are the students?

The people section focuses on identifying who are the students of the training course, and who will be delivering the training. When considering the students, attention should be given to their education background, literacy skills, and experience. The teacher should be someone who has both the technical competence to perform the task, experience to provide legitimacy and context for the training, but who also has a background and ideally a qualification in training and adult education. This means that the best operator may not necessarily be the best trainer.

In the case study, the training provided was for new staff without previous industry experience. With this in mind it may be expected that this training would represent a lot of new information that may overload some students. In this circumstance it would be ideal to provide opportunities to practice driving under the supervision of a dedicated, suitably qualified trainer who can reinforce positive behaviours. It may be expected that these students will take some additional time to demonstrate competent behaviours.

Delivery: What methods are being used?

The delivery section looks at how training is presented to the student, i.e. what are the strengths and weaknesses of the delivery method, and how well this is suited to the students and the content? In most instances effective training will involve a combination of a few different delivery methods, to ensure that the various knowledge, skills and abilities that are required can be developed effectively. A wide range of delivery methods are available. Some of the more common methods include: small group, large classroom, online/e-learning, on the job, self-study, Podcast, video, simulation, case studies, role plays and those provided by an offsite/external provider.

In this case study the content was delivered in a small group environment using a PowerPoint presentation. This format is acceptable for providing knowledge to the student, but is not the most effective choice for developing operational competence. For a practical activity such as tug driving it would be suggested that on the job training, simulation and role plays would have been beneficial to training delivery. This would have the added bonus of providing additional opportunities for the learners, who are new to the industry or poorly trained, to reinforce and practice these newly formed skills in a safe training environment.

Outcome: How is competency assessed?

The outcome part looks at how the organisation can be satisfied that the new employee has the required skills, knowledge and abilities to perform the task safely to the required standard. This is vital as this ensures any failure elsewhere in the training system does not lead to a risk in the operational environment. To do this it is important that the assessment method selected accurately assesses what it is meant to, it does so in a consistent and repeatable manner, and that it meets the needs of the airline, the ground handler and the employee.

Again there are a wide range of assessment methods that can be used, and it is important that the most appropriate methods are used. In most cases final competence will be the result of assessment over multiple assessment methods, over a period of time. This will ensure that it is a valid assessment.

In the case study example the assessment comprised of a single multiple choice question in an exam. It would be expected that such a significant task as driving around an aircraft would typically contain a wide range of questions spread across multiple assessment formats. This may include a combination of multiple choice and short answer questions in an exam, supported by a practical assessment in a simulated environment before receiving on the job training, with final competence determined by an observational assessment. In this case study the lack of a reliable assessment has led to the unsafe condition.

Review: How is the process validated?

Any training system must have a process for validating itself to ensure that it remains relevant. This may involve seeking, and acting on, feedback from students and teachers, benchmarking operation performance and training outcomes against other operators and/or handling agents, and acting on information from third party audits. In the ground handling industry there is a wealth of resources available from various handling agents, airlines operators, airport authorities, and regulators that mean validating the quality of training and assessment is much easier than in other industries.

An effective training system is vital to ensuring a safe and reliable ground operations function. Additionally there is a strong financial incentive to ensure that full benefit is received for training, and by following the complete Effective Training Cycle a ground handler is able to ensure that the costs of training are not wasted.

Alaskan Airlines Flight 536

On 26th December, during loading an inexperienced baggage handler failed to maintain clearance from the aircraft with the belt loader and inadvertently hit the aeroplane’s pressure bulkhead. Failing to spot any damage, the incident was not reported and the aeroplane took off as scheduled. Around 20 minutes into the flight however, during climb to cruise, the damage caused the aircraft to depressurise, requiring a rapid descent and an emergency landing. Subsequent inspection revealed a 12×6 inch hole had appeared between the right side middle and forward cargo doors.

References

- Flight Safety Foundation, Ground Accident Prevention (GAP), http://flightsafety.org/archives-and-resources/ground-accident-prevention-gap.

- Vandel, B (2004). ‘Equipment Damage and Human Injury on the Apron: Is it a cost of doing business?’, Paper presented at ISASI Seminar, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia.

- Clegg, S, Kornberger, M & Pitsis, T (2011). Managing & Organizations: An Introduction to Theory & Practice, 3rd edn, SAGE Publications, London.

- Elk, A & Akselsson, R (2007). ‘Aviation on the Ground: Safety Culture in a Ground Handling Company’, The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 17(1), 59-76.

Biography

Tim Meagher is Ground Operations Inspector with the Civil Aviation Safety Authority of Australia. In this role he works with industry to encourage higher levels of safety within ground operations. He is a graduate of the University of Wollongong with an MBA, and has broad operational and management experience across all facets of ground operations.

Issue

Related topics

Aeronautical revenue, Airside operations, Baggage handling, Ground handling, Recruitment and training

Situations and sample case studies on direct employee feedbacks are very beneficial for ongoing training and result driven outcomes.