A low-cost revolution? The power of the short-haul business model

Posted: 28 March 2017 | James Halsted | Co-founder | Aviation Strategy Ltd | No comments yet

Managing Partner of consultancy Aviation Strategy Ltd, James Halstead, presents the case for change in the airline market.

The short-haul low cost airline business model is accepted and established in today’s market, but can airlines benefit from offering a long-haul low cost model? And for secondary airports that fall outside of main long-haul hubs, could this be an exciting opportunity?

One of the airline industry’s greatest features is that it portrays dynamic growth. As a conduit of physical communication, over the years it has demonstrated that an increasing disposable income and a reduction in the cost of travel, along with a rise in available leisure time, generates growth in demand. The airlines themselves – highly competitive enterprises – have shown that, once released from the shackles of economic regulation, they can be the driving force for innovation. The latest product innovation is that of a new airline business model that targets long-haul low cost operations. It is possible that this new business model could be as disruptive to the established world order within the industry as the introduction of short-haul low cost operations has been; the practice was pioneered by Southwest more than 40 years ago and has since spread throughout the world.

The established short-haul low cost and ultra-low cost airline business model is predicated on adopting the most efficient working practices; short turnaround times; point-to-point services; single aircraft types; efficient capacity, workforce and capital utilisation; as well as the ‘unbundling’ of fares. Taken together these efficiencies enable airlines to offer the customer the lowest possible headline tariff. The ultra-low cost model pioneered by Ryanair in Europe, extended from the original Southwest business model in the U.S., has concentrated on a ‘yield passive/load factor active’ pricing policy – the idea is to fill the plane at whatever price is available.

Join our free webinar: Revolutionising India’s travel experience through the Digi Yatra biometric programme.

Air travel is booming, and airports worldwide need to move passengers faster and more efficiently. Join the Digi Yatra Foundation and IDEMIA to discover how this groundbreaking initiative has already enabled over 60 million seamless domestic journeys using biometric identity management.

Date: 16 Dec | Time: 09:00 GMT

rEGISTER NOW TO SECURE YOUR SPOT

Can’t attend live? No worries – register to receive the recording post-event.

The perceived wisdom, however, is that the long-haul low cost model cannot work. The arguments assert that there is too little differentiation between new entrants and legacy carriers on aircraft utilisation (on long-haul flights so much more of the flight time is in cruise). Furthermore there are uncontrollable factors that hinder the model: turnaround times can be affected by airport curfews and time zone differences; aircraft crews will have to overnight at destinations; and, possibly more important, the existing legacy incumbents have the power to offer the deepest discounts at the back of the bus of very large aircraft.

It is often also cited that charter carriers and inclusive tour in-house airlines already provide this product, notably ignoring the idea that passengers may be attracted by low fares to destinations that may not be part of an IT provider’s portfolio. However, at this point it is worth re-assessing the fundamentals of air travel. This is an industry involved in taking a passenger (or a parcel) from point A (close to where they are) to point B (close to where they want to be) safely, on time and (in the case of a passenger) with his luggage intact, at a price that conforms to their concept of the trouble of enduring the process. This is a commodity business; and from the passenger point of view the airline is a vector and the airport a way-point that is a necessary evil to encompass their end.

There may not be as high a potential for a low cost entrant to reduce costs compared to the legacy network carriers, but there is still significant potential. This arises primarily from the ability to start with an efficient operation on a clean piece of paper: maximise duty rosters; reduce the number of crews per aircraft; avoid legacy pension plans; ensure efficient MRO and distribution; and above all increase the number of seats on the aircraft (Norwegian for example operates its 787-9s with 350 seats). Based on our calculations an efficient new long-haul low cost operator should be able to operate at a unit cost approaching 50% below that of legacy opposition – a figure borne out by recent financial data from AirAsia X and Scoot.

For an established operator to make money on long-haul routes it needs to generate a short-haul feed to connect on to long-haul operations.

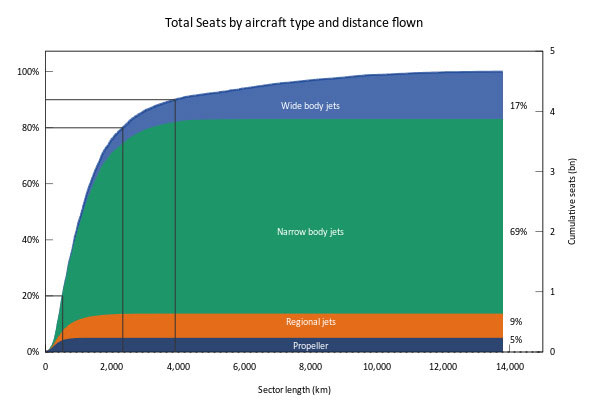

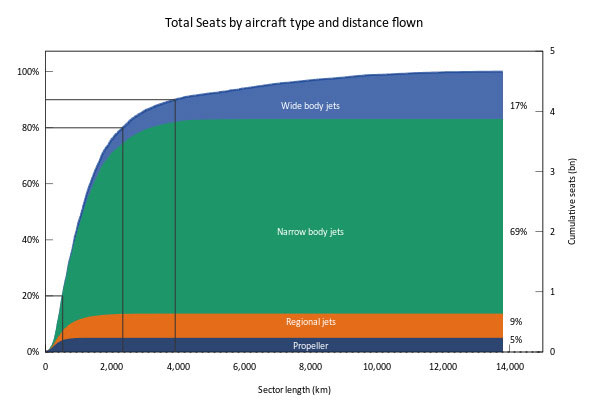

At the same time, it should be pointed out that long-haul services (which we are defining as 5,000km) account for a very small amount of total air transport operations and this makes it a far more competitive segment of the market. The industry has a tendency to measure business capacity and demand in terms of available seat kilometres (ASK) and revenue passenger kilometres (RPK) with implicit reference to the distance travelled which automatically gives extra weight to long-haul routes. In 2016, 90% of all seats were flown on routes less than 4,000km in length, and the majority of these by narrow-body jets, which account for 69% of the seats in the market and of which there are an estimated 430 or so operators worldwide. Wide-body jets, meanwhile, account for only 17% of the total number of seats flown (but 45% of total ASKs) and are operated by 170 different carriers.

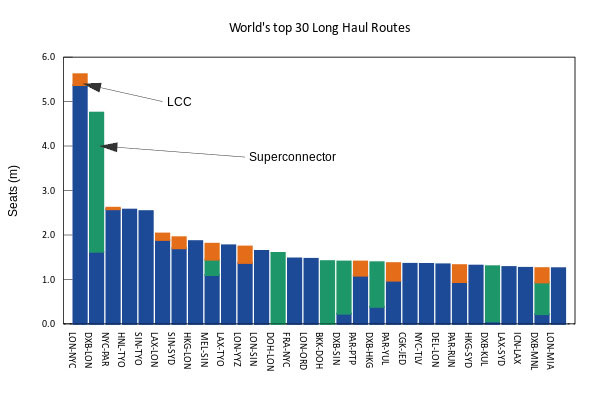

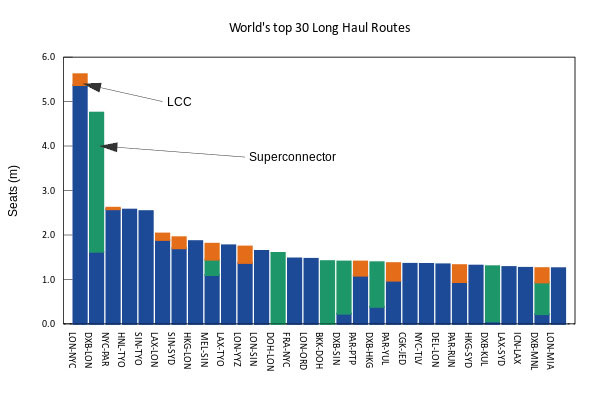

Figure 1: The world’s top 30 long-haul routes

Of the 1,700 or so long haul-city pairs, 245 (20%) account for 62% of the total number of long haul seats, and the top 10% of routes nearly 50% of the total. In terms of major long-haul route areas, the trans-Atlantic stands out as by far the largest, with 140m seats flown, dwarfing the next largest of Europe-Asia and the transpacific (although the Europe-Asia routes have been hit by the development of the Gulf-based super-connectors). There appear to be very few long-haul routes with strong point-to-point demand. This has meant that for an established operator to make money on long-haul routes it needs to generate a short-haul feed to connect on to long-haul operations. Historically this has led to the development of intercontinental hub and spoke networks. Persuading passengers to connect through that hub can involve significant discounts.

So what has changed?

The answer, as usual, is technology. The two main manufacturers have introduced two new twin-engine wide-body aircraft types – the 787 and A350 (on top of the 777 and A330) – that can provide superior range at low unit costs. There are currently some 2,800 twin-engine wide-body aircraft (777, 787, A330 and A350) in service worldwide, of which we estimate 32% are in the hands of operating lessors. The industry is in the process of a period of long-haul fleet replacement, and there are outstanding dated orders for over 2,200 of these types, with expected deliveries averaging 330 a year over the next four years. This represents approximately 12% of the current fleet. It is expected that many of the deliveries will be used to replace ageing and four-engined wide-bodies.

Figure 2: Total seats by aircraft type and distance flown

There may appear to be limited opportunity for new entrants to acquire new aircraft of this type direct from the manufacturers. However, the major operating lessors have orders outstanding for around 215 of these types, mostly for delivery by 2021. In addition, an increasing number of the in-service aircraft will be approaching eight years old – approximately half their useful life in passenger service – and some of these may be expected to become available for remarketing.

In addition, both manufacturers have developed extensions to their short-haul aircraft – the 737 MAX and A321ER – that can easily and relatively efficiently access routes of up to 6,000km, the lower end of the long-haul route spectrum. We have a handful of pioneers: Jetstar in Australia, AirAsiaX in Malaysia and other countries of ASEAN, Cebu Pacific in the Philippines, SIA’s subsidiary Scoot based in Singapore, Canadian Westjet and Europe’s Norwegian. Notably, all rely on some element of transfer feed (which they try to price in as an ancillary fee) and (with the exception of Cebu) provide some ‘premium’ product. Norwegian is even moving towards getting feed from other LCCs at its European long-haul bases. Having started using 787s, Norwegian is now developing transatlantic routes using the 737 MAX it has on order from secondary and tertiary airports on the west coast of America – bypassing the main international hubs.

The short-haul low-cost carriers (LCC) have severely dented the profitability of legacy carriers’ network operations by undermining the business of pricing transfer traffic.

The short-haul low-cost carriers (LCC) have severely dented the profitability of legacy carriers’ network operations by undermining the business of pricing transfer traffic. Moving into long-haul they could have the same disruption on the hitherto profitable long-haul operations. For airports that rely on a large base carrier this may represent a quandary – do you accept to do a deal with a new entrant LCC who can promise high growth while your base carrier plans only modest growth? It is interesting to note that Frankfurt in Europe recently courted and arranged deals with both Ryanair and Wizzair. For a secondary airport outside the main long-haul hubs this could offer an exciting opportunity.

JAMES HALSTEAD is a Managing Partner and cofounder of Aviation Strategy Ltd, a boutique aviation consultancy focusing on all aspects of commercial aviation. James has followed the global aviation sector closely since the early 1980s and was the first investment analyst in London to publish specialist research on the industry some 30 years ago. Over the course of his career he has worked for a number of major investment banks including HSBC James Capel, Salomon Brothers, Hoare Govett, Swiss Bank Corp, Flemings, Crédit Agricole Indosez Cheuvreux, and Dawnay, Day – and was regularly ranked among the top transport analysts. He has been involved with many IPO share issues, trade sales and strategic advisory roles for companies in the sector including British Airways, Iberia, Air France, Lufthansa, Alitalia, Cathay Pacific and Air New Zealand.

Join our free webinar: Revolutionising India’s travel experience through the Digi Yatra biometric programme.

Air travel is booming, and airports worldwide need to move passengers faster and more efficiently. Join the Digi Yatra Foundation and IDEMIA to discover how this groundbreaking initiative has already enabled over 60 million seamless domestic journeys using biometric identity management.

Date: 16 Dec | Time: 09:00 GMT

rEGISTER NOW TO SECURE YOUR SPOT

Can’t attend live? No worries – register to receive the recording post-event.

Issue

Related topics

Aeronautical revenue, Aircraft, Economy, Regulation and Legislation, Route development